Bangladesh approves death penalty for rape, but will it help?

Amid growing anger and widespread protests, Bangladesh’s government approved on Monday the use of the death penalty in rape cases. Led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, the cabinet met online and approved changes to a law that will enable courts to sentence any convicted rapist to execution.

President Abdul Hamid was expected to sign the “Women and Children Repression Prevention (Amendment) Bill” into law on Tuesday, according to Law and Justice Minister Anisul Huq.

The country’s existing laws mandate a life prison sentence for rape convictions, but now courts will be able to choose between that sentence and death. Bangladesh’s parliament wasn’t required to consider the change in the legislation as it’s only an alteration of existing law.

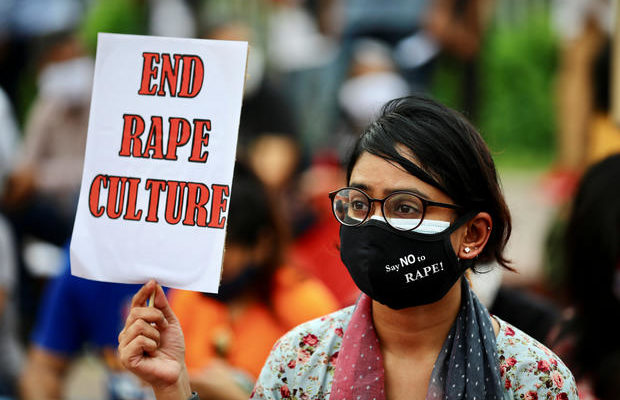

The government drafted and passed the law after weeks of angry, unprecedented protests across the South Asian nation following a series of high-profile rapes.

Anger had been building against the government and the police for perceived inaction in several rape cases for months, but a 30-minute video of a woman being stripped and sexually assaulted by a group of men, which spread quickly across social media, triggered huge protests over the weekend.

The police have now arrested eight suspects for the assault that was caught on camera more than a month ago in Noakhali, about 120 miles southeast of the capital, Dhaka.

Escaping accountability?

While the punishment is severe, several activists who joined the protests in Bangladesh and who have led the campaign for change told CBS News that the government’s move is more a cop-out than a meaningful commitment to protect women.

They note say most protesters never demanded the death penalty, as many don’t consider it a real solution to country’s sexual violence problem.

“The government strategically chose a road that would let them escape accountability,” Umama Zillur, a member of the Feminists Across Generations alliance, who has been fighting gender-based violence in Bangladesh for several years, told CBS News. “We will not accept this.”

Zillur is one of the organizers of the #RageAgainstRape protests that rocked Bangladesh over the weekend. She said the voluntary participation of high school students was unprecedented.

“Nowhere in our demand did we ask for death penalty… because we know death penalty is going to reduce conviction rates, will increase murder after rape, and at the end of the day it’s not going to help us in any way.”

Activists believe rape often goes unreported in Bangladesh because of social stigma, a lengthy justice process, low conviction rates and fear of harassment by offenders.

Shahdeen Malik, a senior advocate (lawyer) at Bangladesh’s Supreme Court, told CBS News that the conviction rate for rape cases in Bangladesh is less than 3%. He said that is due in large part to the country’s police being unable or unwilling to properly gather and handle forensic evidence.

“They’re poorly educated and they are not sensitized,” said Malik, who represents defendants in cases that reach the high court. “Our police is a male dominated force which doesn’t even consider rape a serious crime.”

Zillur and Malik, like many others, believe the government isn’t focused on fighting the root problem as much as it is easing the pressure from an angry public. They see the death penalty as a knee-jerk reaction to the protests.

Taqbir Huda, a Research Specialist at the Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST), noted to CBS News that under existing Bangladeshi law, the death sentence is already an option for gang-rape or rape-murder convictions.

“So death penalty for Noakhali incident was very much an available option,” he said. “The government should introduce reforms that actually tackle root causes behind impunity for rape. The death penalty is not one of them.”

“I won’t be surprised if tomorrow the government decides to crack down on the protesters, telling them, ‘why protest when we have already met your demands?'” said Malik, the Supreme Court lawyer.

“Rape has become a culture”

Rather than the death penalty, protesters have called for systemic change in the country of 170 million people, where advocacy groups estimate that on average, almost four women are raped every day.

Rights group Ain o Salish Kendra, which keeps a tally of rape statistics in the country, says 975 women have been raped this year already, one fifth of them subjected to gang rape. Government data doesn’t list the number of rapes specifically, instead lumping them together with a broad range of crimes against women under the category of “women and child repression.”

Huda, the researcher and activist, said some of the key demands to address the problem include a law to protect witnesses; a wider definition of rape that includes marital rape; and government efforts to boost national awareness of the implications of sexual violence.

“We want long term solutions, not a situation where 20 years down the road we will be still protesting on the streets,” said Huda.

Protest organizers were to meet Tuesday to plot their next steps to keep pressure on the government.

“The problem is not that we don’t have strong laws, the problem is that rape has become a culture in our country,” Meera Sushmita, a student who participated in the weekend protests, told CBS News.

“It’s so common and normal in Bangladesh for women being blamed for rape,” she said. “People believe women are raped because of the way they dress, which is [considered] too modern for this country.”

Sushmita, a member of an anti-rape network, is now focused on raising awareness through a public campaign, trying to educate people about consent and the seriousness of rape. She and friends spent Monday painting murals and slogans on walls around Dhaka, trying to get the message across.

Many young women in Bangladesh, including Zilur and Sushmita, have taken hope from the protests and the response to them. Now they’re more determined than ever to keep pushing for the kind of change they say could make a real difference.